TW-Police Violence, Sexual Assault

"With my guilt-free takes on the Classics,

there's no need to separate the Art from the Artists.

You can throw them both in the garbage."

SIGH (image from Kitchen Sink Press)

Lil' Abner was started in 1934 by Al Caplin (later Capp) who had finished a two year tenure working as a ghost on Ham Fisher's boxing strip Joe Palooka, which is a story for another time. The plot involved a dumb hillbilly type visiting New York, where he was beset upon by various city-things. Eventually his mother had to bail him out of various societal issues. All this happened while a young lady named Daisy Mae pined for him back in the hills of Dogpatch, KY.

A very early example from GoComics.com. Unfortunately this blog format does not allow cropping.

The strip proved popular. Lil' Abner wound up in several more instances of societal hijinks before Capp decided to put him through his hijinks at home. Daisy Mae became much less stoical (and much more sexualized, thanks in part to ghost artist Moe Leff, an early link in a long chain of Capp ghosts) during this time, actively chasing after Abner. Indeed, the strip's drive to a nationwide popularity that would include merchandise, a Broadway musical, two film adaptations and a theme park was fueled in large part by Sadie Hawkins Day, an In-Abnerverse holiday that may still be semi-celebrated in obscure pockets of the United States.

The holiday was simple enough. It involved a "race" of sorts that intrigues one as a small child, then frankly disgusts one as a larger child: First the men of Dogpatch would take off running, and then the women of the town would take off running after the men. If a woman caught a man, the man would be forced to marry her. The holiday, if any of you feel like setting a reminder to sleep in, now falls on the 13th of November (It was first observed in 1937, possibly on the 15th, and Capp would just have it happen on a random day in November after that). By 1940, the year the first Abner film was made, the formula was mostly complete, and Li'l Abner became exceedingly popular. The holiday began to be celebrated in colleges and high schools, either as reenactments of some kind or as dances.

After this, the strip settled into a formula: Sometimes Abner would go forth into the city again, other times he would avoid Daisy Mae. Various other characters, like Earthquake McGoon, would wander in and out at Capp's will.

And Capp's will was a strange beast indeed. In 1948 was introduced the Shmoo, a blobby species that could produce anything mankind needed out of itself. Unfortunately, shmoos and conservative capitalist corporations could not coexist, and so the Government eradicated the cute little buggers.

If you should read the above paragraph and detect a leftist slant to it, you'd be right. Capp was something of a center-left figure (I.E. a Truman/Stevenson Democrat) in 1948 and his politics were leaking into Abner like a sieve. The public greatly enjoyed the tale of the Shmoos as well as the Shmoo's design, and in short order a great amount of merchandise was produced. They were soon drilled into the zeitgeist. Such an icon of the Truman Years did these creatures become that one piece of Shmoocana was used in an episode of M.A.S.H (set around the same time) as a scene-setter. Indeed, the Shmoo became a tactic in American Diplomacy:

In 1948 Capp worked with the 17th Military Air Transport Squadron to airlift chocolate-filled Shmoo dolls and life-size inflatable Shmoos into Berlin...An article about the Shmoolift in Life magazine rhapsodized about the “CAPPitalistic lessons” that the captive Teutonic commies might learn from the man who had invented his own prosperity.

--Daniel Raeburn, The Brand Called Shmoo

Shmoo Merchandise & a East Berliner with a Shmoo (Denis Kitchen Online)

Capp would continue to deal in strange, small creatures, all of which posed some threat to the US government, for the rest of the strip's run. The best remembered of these in the history books are the Kigmies, who love to be kicked by humans until they begin to kick them.

Capp's liberal satire won the hearts of '50s intellectuals (along with Pogo, by Walt Kelly, which will be discussed later in this article) and he began to mock corrupt politicians or political pretenders with characters like General Bullmoose.

Capp let Daisy Mae catch and marry Abner in 1952, and for this the strip got on the cover of Life.

Reason for shirtlessness unknown. Capp began to take his brand of liberalism to Television. Lil' Abner was made into a musical comedy in 1956, and the musical comedy was made into a movie in 1959. We'll get into all that another time, but it is worth pointing out that the musical comedy stayed true to the strip's liberal ideals. The strip, however, would not.

Sometime during the Johnson administration, Lil' Abner began to skew conservative. His reason for this was his disgust at the counterculture of the 1960s and the people within those movements. He saw these young college students as hypocrites--born of privilege but trying to speak for the unprivileged, or even trying to act unprivileged. (This may or may not be true in some cases, don't tell me what you think.) Capp came from a poor Bostonian background, and claimed that the shift came from a desire to uphold "the poor son-of-a-b*tch who worked." Al Capp was a wealthy man by this point, a privileged person in his own right. We shall see the fallout from this swing shift later, but first, a gallery of Abner's Conservative Era:

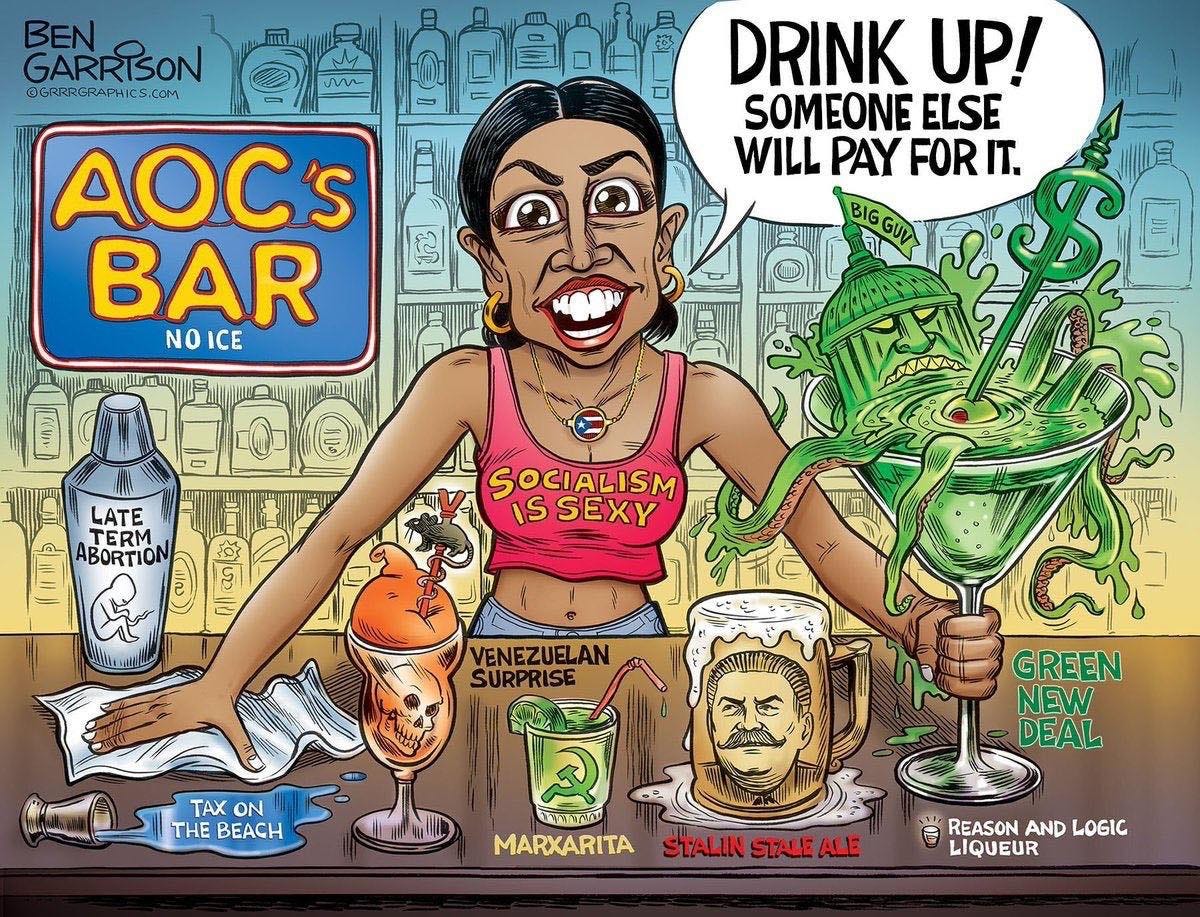

For comparison's sake, here's how modern conservative cartoonist Ben Garrison draws those he disagrees with:

Note not only the smug grotesque qualities of the line in the above examples, but also the fact that the enemy figures are, occasionally, heavily sexualized.

In 1969 Al Capp claimed in a letter to Time Magazine that his caricatures of college students were of the minority of the student population, "not the dissenters, but the destroyers." He never did show these "good dissenters," at least not much. This is, objectively, a failure both at satire and writing. Most writers do not have to write into Time Magazine, independent of their work, to tell everybody what they meant. And if he wanted to make a point about a minority of college students who were violent hypocrites, why did he not show or barely show these "good dissenters?" This concept probably did much to vilify all the Campus Movements in the eyes of the "Silent Majority." Richard Nixon (along with other conservative politicians) made Capp a personal friend, and one wonders if, when the military police stormed peaceful campus demonstrations, those dirty, violent Abner college students were at the back of their mind.

Indeed, Capp was suddenly a conservative social lion. He was hosting television programs like the one illustrated below, lauded by many, and pals with a sitting president. He could spout off on politics whenever he wanted, often on national television. He submitted articles to many different magazines. He became an upholder of American Conformism, even yelling at John Lennon and Yoko Ono during the Bed-In. The comic strip remained popular and was even made into a theme park in Arkansas in 1967. Life was suddenly very good for Capp.

Note: The program asked whether blondes did, in fact, have fun. Shall humanity ever know how many after-dinner martinis were consumed during the duration of programs like these?

Capp even went on a college speaking tour, where he lectured those students that agreed with him. It was on these tours that Capp ran into the trouble that would hasten the end of these glory days.

The incident, hushed up for three years by the university administration, is both ironic and significant. For Capp's scathing denunciations of college students and their morals have made him one of the most controversial commentators of the day...It gives us no pleasure to make these revelations about a man whose legendary "Li'l Abner" cartoon creations have amused millions of Americans for generations. But Al Capp today is much more than a gifted cartoonist and a brilliant humorist. He is a major public figure, whose views reach and influence millions. He even seriously considered running against Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass. Therefore, we believe the public has a right to any information which may bear on his qualifications to speak, particularly when the incident involved is so obviously relevant to the selfsame subjects on which he has been holding forth.

--Jack Anderson, from the April 22, 1971 article

BRIT HUME: ”The Post” – ”The Washington Post” didn’t run it. The Boston paper, whichever one we had then didn’t run it. A lot of papers didn’t run it.

BRIAN LAMB: A Chicago paper out there --

BRIT HUME: I don’t remember, but I can’t remember now. But it might be in the book, but ”The New York Post” ran it. We found that the Al Capp lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the ones that – the minute ”The New York Post” hit the newsstands up there, they were all bought up. So, he did everything he could to try to cover it. Now, one of the things – interesting things that happened was that the story ran in a little newspaper out in Wisconsin in Eau Claire, where there’s a branch of the University of Wisconsin.

It so happened at that very moment that a young woman had had a similar encounter with Mr. Capp out there and she like a number of women across the country, we later came to learn, was agonizing with the local prosecutor about what to do. He didn’t – he was indignant about what had happened and outraged, but there was a question of are you going to put this – her word against his testimony and he’s a famous guy. And you going to put her through that for the sake of something that she managed to wriggle out of anyway. And when that story hit, her resolve was – look, this is obviously happening elsewhere. We got to do this. So, he was charged out there. And an extradition measure was taken. And Al Capp was on the verge of being extradited to Wisconsin to stand charges of assault. And as – I don’t remember all the details, but I think he pleaded out and got it over with. And, basically, he was really never heard from again.

Critics of this blog will be quick to point out many things Capp did for gender equality within his industry, but before they do I would like them, and anyone really, to read this excerpt from Jean Kilbourne's harrowing account of being one of Capp's victims:

...It seems clear he was a misogynist. However, he did resign from the National Cartoonists Society when male colleagues wouldn’t admit a female member. Of course, many offenders, such as Louis C.K., have presented themselves as feminists. Harvey Weinstein posed as a champion of women’s rights and donated generously to female politicians. It’s impossible to know whether this was a disguise, a front, or evidence of a split in their psyches, a kind of Jekyll and Hyde situation.

Capp attempted to blame the whole thing on the "Radical Left," but was stripped of many of his platforms, was convicted of Attempted Adultery in Wisconsin, and was no longer the potent political pundit he once was. He poured the last of his vitriol into Lil' Abner, which faded into obscurity, ending in 1977 when Capp refused to continue it. He died two years later.

How have the historians of the Strip Industry remembered him? Most of the time, they glorify him. In The Comics, by Brian Walker, devotes two sections to Capp, pre and postwar, each with about ten to fifteen examples. Rick Marshall includes him in his America's Great Comic Strip Artists. In The Comics, one of Capp's indecencies is mentioned almost in passing, but it comes up nowhere in Marshall's volume. In The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics, printed after the indecencies, Capp still has some space. Even Al Capp: A Life to the Contrary, a book that makes similar points to this article, upholds the strip as a masterpiece.

But, artistically, does he deserve it? Does he deserve the accolades and praise that historians have given him?

Separating Art from the Artist is an old concept in which Art is immutable, and uses the Artist like a channel to move to the world. But any realism in philosophy would show this to be false in many cases. Art is the idea of the Artist, and is sprung from the Artist's entire psyche. Neuroses, cravings personal weakness; all are reflected in the Artist's Art. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Abner.

Abner pivots around the sexual tension between a willing woman and a mostly unwilling man. It is obvious Capp had fantasies about being pursued by designing women, and it is even more obvious he made Li'l Abner, the character, his avatar. The strip would give Jung and Freud something to think about.

The reason we know Li'l Abner was a self-insert, or, more pejoratively, "Gary Stu" character, is this drawing from Comics and Their Creators, published before Capp presented himself as a caustic curmudgeon, possibly by Capp himself, or one of his ghosts:

"Any resemblance to any actual character, living or dead, is purely accidental!"

It was obvious that Capp was, essentially, running his self-insert hillbilly erotica in hundreds of newspapers, and, if anything, this feat was celebrated at the time. Images of the helpless Abner struggling whilst slung over the shoulder of the feral, buxom "Wolf Gal" attempting to transport her prey back to her cave (and other awkward images) litter the strip. Capp could use Abner to act out other fantasies, one series circa 1945 showed Abner as the janitor at the radio station. When Abner cleaned the recording booth, he would pretend to make sensual speeches professing his secret love for Daisy Mae. The microphone was still plugged in, and Abner soon became the station's greatest attraction as lovestruck women (including the actual lady in question) tuned in to hear his midnight confessions. Capp was able to mock himself sometimes, but the fact still remains that Abner was a highly personal, perhaps too personal, work. Many critics regard this as a quirky asset if they regard it at all, but there was a significant dark side to it.

Recall the way Capp drew some of the female college students and then recall his indecencies. Here's another picture for further evidence:

1971, the year of the Anderson article, From

Comics Commentary. The lady in the green shirt is a Vassar student.

The evidence seems to show that Capp had some sort of twisted attraction to the very women he maligned in the comic strip. The images of buxom hippies that are sprinkled throughout his "satires" are sadly telling (though the strip was drawn by ghosts, Capp still directed the writing, and, presumably, the anatomy). Further evidence of this comes from Capp's defenses of himself after the Wisconsin incident and the Anderson article:

She was a “left-wing” girl, Capp said, a “do-gooder determined to remake me.”

-The Brand Called Shmoo, Daniel Raeburn

Capp's response to Anderson was a pleading, "You know how these college babes are," which turned to panic when he saw Anderson's face turn red with rage.

--Jack Anderson Files Added to Gelman, Jake Swirsky

He seemed to think that the conflicting opinions of him and college women meant that they wanted him, that they were asking for it. It is surprising that he was allowed to go on the college tours at all, seeing how he ordered female college students drawn.

Somehow it is claimed in the history books that Capp did not tolerate hypocrisy, as in Markstein's Toonopedia. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that Capp was, himself, a hypocrite. According to Harvey's dual biography of Capp and Ham Fisher, Hubris and Chutzpah:

{Britt Hume} also recognized the deliciously scandalous irony in the situation: all the time Capp was rampaging against the lax morality of the student left, he was “a goddam sex criminal,” attempting r**e.

There is no way that Capp is anything but a hypocrite. There is abundant evidence for this, not just his personal change of opinion. A change of opinion does not a hypocrite make, but an active subversion of an opinion does. And so Capp is a hypocrite: denouncing the low morals of the youth and then assaulting them.

Another record of his hypocrisy is his introduction to ARF!, a 1970 collection of Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie, once the best-known comic strip to have heavily conservative leanings. Capp describes the time he met Harold Gray (hypocrisy highlighted in yellow:)

"He said, 'I know your stuff, Capp. You're going to be around a long time. Take my advice and buy a house in the country. Build a wall around it. And get ready to protect yourself. The way things are going, people who earn their living someday are going to have to fight off the bums.'

I remember that I was shocked, and a bit amused at his words. But not surprised. Gray was known to us liberal young snots...as a bitter old man...I had nothing to fear from the "bums." I had been on the bum myself. In the thirties, there weren't many chances for anyone to earn a living, and almost none for a kid with one leg. When a chance did come along, I grabbed it, and held on for dear life. I knew that bums were eager not to be bums...[and] wanted to earn a living...

But bums have changed. And my attitude to Harold Gray has changed.

I bought a house in the country, as he advised me to. I didn't build a wall around it.

In the last five years, it has been broken into, several times. I live on a pleasant, historic street in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There have been two attempts to rob it in the last five year, one attempt at r**e in our garage...

There have been in the last few years, murders, muggings, and molestings in our neighborhood. It is no longer safe to walk on my street after dark...

It has taken me thirty years to realize what a superior understanding of our even-then developing ruling class, the bums, Gray had...

We are fleeing from our cities, buying homes in the country, and preparing to protect ourselves...

If Gray's attitudes were old-fashioned in his time, so to, then, are personal dignity, manners, and respect for law today. And now ask yourself this: Can any new society be built without those attitudes?"

For all his crowing about personal dignity, manners, and respect for the law, Capp was noticeably bad at upholding the bargain. Capp thought that the criminals of his day were decent under the skin, and that the homeless of his day just needed a chance, but thought that the vagrants and criminals of the 1970s were irredeemably evil, a strange conclusion. He had the opportunity to pull himself up by his bootstraps, but was too short-sighted to realize that so many of his famous "bums" could not access the opportunities he claimed were offered so regularly. His introduction to Arf! shows true hypocrisy.

Satirically, the strip is also lacking, specifically toward the end. Capp's drawings of hippies make wild assumptions on the nature of the counterculture movement, and it is clear that he never did much research upon their goals. His caricature of Joan Baez makes the assumption that she was pro-violence and inciting student uprisings. He drew her as "ugly" as possible, for, as Capp likely thought, when a woman is "ugly" they cannot hold correct opinions. When Joan Baez took issue with these libels, Capp claimed it was free speech that she would have to prove that she was as ugly as her caricature (even though the caricature was literally named Joanie Phoanie.) Capp was not a satirist, but a name-calling hypocrite.

And in syntax, Abner does not scan. *Gulp*s and *Sob!*s were written right into the panels, the dashes flowed like the mighty Scioto, the hillbilly talk felt clunky and forced.

It must needs be remarked, however, that Abner did have a large effect on the American Zeitgeist. People followed the events, reenacted the holiday, bought the shmoos, and submitted art and photos for the contest to draw "The Ugliest Woman" and find "The Sweetest Face," to define the look of two characters, Lena Hyena and Nancy O.

The winning Basil Wolverton entry in the Hyena contest (Wikimedia)

It is fine to provide examples of Abner in history books with a statement on its impact on American Culture, however, due to its hypocrisy and obscene levels of self-indulgence, it cannot be upheld as a masterpiece.

SOURCES USED

Books:

100 YEARS OF AMERICAN NEWSPAPER COMICS: an illustrated encyclopedia. Comp. Horn, Maurice et al. Gramercy Books, New York. 1996.

AL CAPP: A LIFE TO THE CONTRARY. Aut. Schumacher, Dennis, and Kitchen, Denis. Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2013.

AMERICA’S GREAT COMIC STRIP ARTISTS. Comp. Marschall, Richard. Roundtable Press/Abbeville Press, New York. 1989.

ARF! THE LIFE AND HARD TIMES OF LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE (int.) aut. Al Capp, Arlington House/ Bonanza, 1970.

THE COMICS: the complete collection. Comp. Walker, Brian. Abrams, New York. 2011.

COMICS AND THEIR CREATORS, Comp./Aut. Sheridan, Martin, et al. Pref. by Towne, Charles Hanson. Luna Press, New York. 1971.

THE SMITHSONIAN COLLECTION OF NEWSPAPER COMICS. Comp. Blackbeard, Bill, and Williams, Martin. Fwd. by Canaday, John. Smithsonian Institution Press/Harry Abrams Inc. 1987.

Websites:

America Magazine: When Satire Sours (O'Brien, Dennis, 2013)

The Atlantic: Just How Bitter, Petty and Tragic was Comic Strip Genius Al Capp? (Heller, Steven, 2013)

Arkansas Road Stories: Dogpatch USA.

The Baffler: The Brand Called Shmoo (Raeburn, Daniel, 1999)

Bookforum: Children of the Cornpone (Schwartz, Ben, 2013)

Comics Commentary: Al Capp's S*x Scandals (2012)

The Comics Journal: Hubris and Chutzpah, part 8 (2019)

C-Span: Q&A with Britt Hume (Lamb, Brian, 2008)

The Daily Cartoonist: First and Last--Lil' Abner (Degg, D.D., 2018)

Denis Kitchen Online: Shmoo Facts (Kitchen, Denis, 2004)

Don Markstein Toonopedia: Li'l Abner (Markstein, Don, 2000-08)

The G.W. Hatchet: Jack Anderson Files Added to Gelman (Swirsky, Jack, 2010)

Hogan's Alley: Dogpatch Dispatch: My Encounter with Al Capp (Kilbourne, Jean, 2020)

People: Goldie Hawn Remembers the Casting-Couch S*xual Predator who Left Her in Tears at 19 (Cagle, Jess, and Russian, Ale, 2017)

UPI: Al Capp Denies his Character "Joanie Phoanie" looks like Joan Baez (1967)

Article:

"AL CAPP HUSTLED OFF U OF A AFTER COEDS CHARGE HE MADE INDECENT ADVANCES", Aut. Anderson, Jack, 1970.

No comments:

Post a Comment